Help: How to create a game

– Creating a game step-by-step

Game Graphics

- Inserting graphics to a game:

images and animations

Don't miss

What else you should know about the graphics of the game

The graphics of the game have one special feature, which you should keep in mind: It is not always shown in the same form as it was created. Why? Because the game can run on many different devices - with different sizes and with different screen resolutions (number of pixels). Therefore the GameStylus system has to adjust the graphics. How exactly?

(If you want to create your game for just a couple of friends, don’t worry about the details described in paragraph 2. But if you mean it seriously with games, you should know about them.)

1) Pay attention to small details

If the player plays the game on a small screen with low resolution, fine details may be invisible or less visible. If the details are not essential for the game, no problem. However, if you place a stone on the scene about the size of 1x1 pixel, which the player has to pick up and use, it can be a problem. How big - or small – the objects on the scene should be? Any graphics can be reduced up to 4: 1, i.e. with the greatest reduction an item of the size 4x4 pixels can be reduced to just 1x1 pixel.

2) Be careful with variable objects in animations

If there is anything on the scene which has to change, there is another problem that must be avoided. What? Let's start with a brief explanation of the two basic possibilities of movement/change of an image/object in the scene (if something is not clear from the text, pictures will tell you more):

If there is anything on the scene which has to change, there is another problem that must be avoided. What? Let's start with a brief explanation of the two basic possibilities of movement/change of an image/object in the scene (if something is not clear from the text, pictures will tell you more):

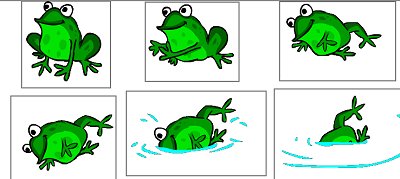

a) The object is changed so that no part of it will stay the same or in the same place: Perhaps the character moves, an arrow flies...

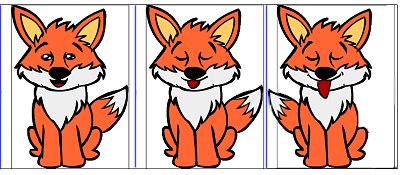

b) The object is changed so that a part of it is still the same: A figure stands still, just smiles (i.e. only the mouth changes), an box opens (most of the box is still the same and in the same place, only a part of it - the door - changes - opens).

It is evident from the images: Each image of the leaping frog is completely different, i.e. when the animation runs, no part of the frog stays in the same place in the next step. But see the fox – when the animation runs, the fox stays almost unchanged, the change occurs to the tongue and eyes.

In the case a) there is no problem. In case b) there may be. If it is possible, avoid this kind of animation. And if it is not possible? And why is there any problem?

In the case a) there is no problem. In case b) there may be. If it is possible, avoid this kind of animation. And if it is not possible? And why is there any problem?

When you draw two identical characters – like the foxes differing only by the tongue - and when the animation frames are put over each other in the editor - everything looks perfect. But what about in the actual game? If the images are reduced to a smaller screen, it may happen that each of the images are reduced slightly differently and in the resulting animations, not only the tongue changes, but various other parts of the frames as well. And it won‘t look good. How do you prevent it?

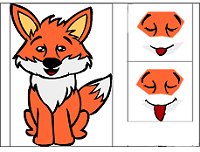

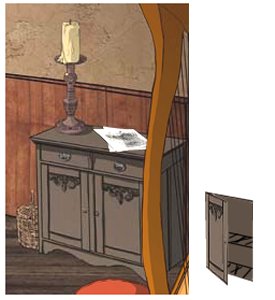

A) The best way is to animate just the changing part of the image. The fox sticks out her tongue? Then put the figure in the scene as a static object and use only animated frames of the tongue. Do you need to open the cabinet doors? Then draw the cabinet as a part of the background and the animation opening the door will not include the entire cabinet, but just the door.

You can see it on the image here: Now the fox is shown as a fixed object in the scene and the animation frames contain only the tongue and eyes. The pictures have no common part, so if any reduction of the image occurs, nothing terrible happens (the white background is set as transparent). In the second picture you can see a cabinet which is a part of the background and the door is painted separately as an object (and there is, of course, the interior of the cabinet visible as well when the door is open).

You can see it on the image here: Now the fox is shown as a fixed object in the scene and the animation frames contain only the tongue and eyes. The pictures have no common part, so if any reduction of the image occurs, nothing terrible happens (the white background is set as transparent). In the second picture you can see a cabinet which is a part of the background and the door is painted separately as an object (and there is, of course, the interior of the cabinet visible as well when the door is open).

B1) If for some reason you cannot use the method A, expect to follow a little more complex process. You can place each animation step in exactly the same image (same size, same location of the graphical object) and not to use sub-images.

B2) Alternatively, let’s suppose you have all the steps of the animation in one image and you are using splitting of the image as described in the article about graphics for games. If the individual steps of the animation must include elements that are the same in all of them, you must follow these rules:

I) The images must be absolutely identical (except the changing part); if the fixed parts differ even within a single point (pixel), the animation simply won’t look good.

II) Choose any point of the images which is identical in all of them. Move the entire image so that the point is at a coordinate that is divisible by the number 8 (for example 8, 16, maybe even 160 or 320, but not 19, because 19: 8 = 2 remainder 3 (since 2x8 = 16; +3 = 19)). This must be true for both x and y coordinates. Follow this rule for all steps of the animation.

II) Choose any point of the images which is identical in all of them. Move the entire image so that the point is at a coordinate that is divisible by the number 8 (for example 8, 16, maybe even 160 or 320, but not 19, because 19: 8 = 2 remainder 3 (since 2x8 = 16; +3 = 19)). This must be true for both x and y coordinates. Follow this rule for all steps of the animation.

III) When cutting the sub-images the cutting must be identical for all frames. If the cutting frame is 50 points before the point mentioned above in the first sub-image, then it must be 50 points before the same point in all other sub-images as well.

It is apparent from the first picture of the fox: Imagine for a moment that the last fox has the same tail as the previous two foxes. Then the simplest way how to obey the rules is to place the top-left point of the ear (which is apparently unchanged in all steps) on the coordinates x=8, y=8. For the second image y=8, x=144, and for the third image y=8, x=288. And the splitting lines are tightly at the ear.

If the fox at the third sub-image has the tail on the left side - as drawn there, we can’t crop the foxes as indicated by the grey lines (because we would cut out the tail), but as indicated by the blue lines. Note that the blue line again has the same distance from the foxes for all the invariant parts of the sub-images - in our case from the left ear.

Finally...

We know that this part is quite complex; given the diversity of devices on which your game will be probably run, and unfortunately, these details need to be known and followed. It takes but a little practice, as you can see. You can avoid most problems if the consecutive steps of an animation don’t have any fixed parts.

In the text there are used pictures from Lukas Balcarek (frog, fox) and Viky Machacku (room with the cabinet) from the upcoming games created in the GameStylus system.